My Love Affair With Pen Computers

(Pen Computing #5, April 1996)My love affair with pens began in 1991 after reading an article on the GRiDPad pen computer. Being a PC person from the early beginnings, I was enamored with the concept of a small, keyboardless computer that I could actually carry with me. All those dreams of Start Trek like devices came rushing into view and I immediately began to collect all I could find about pen computing.

After several weeks and numerous phone calls to GRiD, I discovered

that my own company, Consolidated Edison of New York, had actually done some

research in pens and had possession of a few GRiDPad computers. I managed to

reach the manager in charge of the small pen project and convinced him to let me

borrow one of those miracles.

After several weeks and numerous phone calls to GRiD, I discovered

that my own company, Consolidated Edison of New York, had actually done some

research in pens and had possession of a few GRiDPad computers. I managed to

reach the manager in charge of the small pen project and convinced him to let me

borrow one of those miracles.

A few days later it arrived. The GRiDPad was a marvel to behold. It weighed about five pounds, had a greenish reflective screen, two PCMCIA Type I memory slots (very rare then!) and a tethered pen. Though it only had a 8088 chip, the pen demo programs captivated me. I did a little more digging and found my company's Information Systems resident expert on pens. We soon became friends, probably because I was the only one he knew who was even remotely interested in this obscure area of personal computing.

So my newfound IS friend explained how GRiD and the GRiDPad device had pretty much been the only real (as in actully available) game in town since 1988. He introduced me to the PenPal development environment and showqed me how easy it was to develop applications for DOS based pen machines. I borrowed his PenPal system for a while so I could explore pen development on my own.

For the next few days I was deep in a world of radio buttons, pick lists, text recognition boxes, and LapLink. I designed a couple of small applications for use in my daily activities and used the unit extensively for about four weeks. My colleagues saw me carrying the GRiDPad around all day and I enthusiastically preached its virtues. I didn't tell them about my growing depression. The GRiDPad's screen was hard to see, the unit was slow, it had little memory, and getting data in and out of the unit meant you had to be a LapLink expert.

It was clear that pen technology had not yet reached the level of maturity needed to make it truly useful. After a month of pen computing, I returned the little GRiDPad. But I retained my vision, my enthusiasm, and a pen computing friend in Vinny who continued to share his pen experiences with me.

Other pen systems began appearing on the market. GRiD itself was pushing

its new PalmPad, a very small, almost wearable, DOS-based pen machine whose

strongest suit was a ruggedized and weather-proofed case. But imagine our

surprise (and embarrassment) when a sample PalmPad literally went up in smoke

when getting wet during a demonstration for a company vice president in an

underground facility.

Other pen systems began appearing on the market. GRiD itself was pushing

its new PalmPad, a very small, almost wearable, DOS-based pen machine whose

strongest suit was a ruggedized and weather-proofed case. But imagine our

surprise (and embarrassment) when a sample PalmPad literally went up in smoke

when getting wet during a demonstration for a company vice president in an

underground facility.

During that same period we established an ongoing relationship with

MicroSlate, a Canadian engineering firm with really cool hardware. MicroSlate had

just introduced its Datellite pen computer, a very rugged, modular unit with a

touch sensitive screen and a lunchbox design. The thing was downright ugly but

rock solid. A MicroSlate sales representative actually tossed it down hallways in

a vivid demonstration of the computer's durability. MicroSlate had substantial

pen computer design and engineering expertise and offered to design a custom

machine to ConEd's specification. Alas, such an investment was far too radical

for a conservative company to accept.

During that same period we established an ongoing relationship with

MicroSlate, a Canadian engineering firm with really cool hardware. MicroSlate had

just introduced its Datellite pen computer, a very rugged, modular unit with a

touch sensitive screen and a lunchbox design. The thing was downright ugly but

rock solid. A MicroSlate sales representative actually tossed it down hallways in

a vivid demonstration of the computer's durability. MicroSlate had substantial

pen computer design and engineering expertise and offered to design a custom

machine to ConEd's specification. Alas, such an investment was far too radical

for a conservative company to accept.

The pen computer spark came alive again in May of 1992 when Apple Computer's John Sculley held up this little back box the size of a paperback on a TV show and told the world of his grand vision. Few viewers knew that that particular little box only ran for about 20 minutes on a fresh set of AAA batteries, or that some naming consultants had suggested calling it the ZippyPad. Well, it would be another year before I got my own ZippyPad.

By December 1992, GRiD was promoting its new Convertible pen computer. It

ran Windows and provided access to pen-enabled Windows applications. Due to its

ingenious design it was a pen slate when closed, but the screen pivoted upward at

the click of a switch to reveal a complete laptop keyboard. The system weighed

only 5.5 pounds, and an extended battery promised almost three hours of power.

And there was a big 120MB hard disk. I finally got my hands on GRiD Convertible

three days before Christmas of 1992. It came with a suite of pen applications

developed by the now defunct Slate Corporation. I used these scheduler and

notebook applications everywhere I went for the next six months. I had gotten two

batteries and worked out a strategy to allow me to use the system throughout my

business day. In a few weeks I had amassed almost five megabytes of data within

the suite of pen applications alone. It was pen nirvana. I would be at a meeting

and be able to take notes, check my schedule, verify those budget figures, make a

note to my secretary and, during moments of extreme stress, play a game of

Minesweeper.

By December 1992, GRiD was promoting its new Convertible pen computer. It

ran Windows and provided access to pen-enabled Windows applications. Due to its

ingenious design it was a pen slate when closed, but the screen pivoted upward at

the click of a switch to reveal a complete laptop keyboard. The system weighed

only 5.5 pounds, and an extended battery promised almost three hours of power.

And there was a big 120MB hard disk. I finally got my hands on GRiD Convertible

three days before Christmas of 1992. It came with a suite of pen applications

developed by the now defunct Slate Corporation. I used these scheduler and

notebook applications everywhere I went for the next six months. I had gotten two

batteries and worked out a strategy to allow me to use the system throughout my

business day. In a few weeks I had amassed almost five megabytes of data within

the suite of pen applications alone. It was pen nirvana. I would be at a meeting

and be able to take notes, check my schedule, verify those budget figures, make a

note to my secretary and, during moments of extreme stress, play a game of

Minesweeper.

Disaster struck during a meeting in August of 1993. I had just taken a new

position in my company and we where at a brainstorming session with some of my

new clients. I was taking notes when I detected a faint smell of ozone and a

flicker on the screen. Within minutes the computers response to pen input became

erratic the backlight went dead. I would have to ship the unit off to be fixed

and all my precious pen data was stuck in the machine because it only worked in a

pen machine. My critical data would be lost for the entire time it was out of my

hands. In desperation I backed up the data (not easy without backlight) and

purchased a slightly used NCR 3125 pen computer (The modl shown on

the left is actually a 3115). It only had a 20MB drive but it

was enough for Windows for Pen and my pen stuff. I used the NCR for two weeks. It

was a step back in technology. The non-backlit screen was difficult to read, the

screen was smooth as glass and writing on it felt like, well, writing on glass.

The battery barely held up for 1 hour of continuous use.

Disaster struck during a meeting in August of 1993. I had just taken a new

position in my company and we where at a brainstorming session with some of my

new clients. I was taking notes when I detected a faint smell of ozone and a

flicker on the screen. Within minutes the computers response to pen input became

erratic the backlight went dead. I would have to ship the unit off to be fixed

and all my precious pen data was stuck in the machine because it only worked in a

pen machine. My critical data would be lost for the entire time it was out of my

hands. In desperation I backed up the data (not easy without backlight) and

purchased a slightly used NCR 3125 pen computer (The modl shown on

the left is actually a 3115). It only had a 20MB drive but it

was enough for Windows for Pen and my pen stuff. I used the NCR for two weeks. It

was a step back in technology. The non-backlit screen was difficult to read, the

screen was smooth as glass and writing on it felt like, well, writing on glass.

The battery barely held up for 1 hour of continuous use.

Fortunately, my old pen pal Vinny from IS heard of my misfortune and gracefully

agreed to let me test drive a brand new Toshiba T200. By then Vinny was working

for me, so I suspect his motives were advanced by his employment status. Of

course, he also knew that I would test the unit to death. The T200 was a

beautifully crafted computer, with smooth rounded corners, and barely larger than

its 9.5-inch diagonal monochrome VGA display. The Toshiba used an NiMH battery to

give it longevity. And that it would have had the Toshiba engineers kept it a

decent size. Instead they reduced the battery to the size of a pack of

cigarettes, far too small to keep the unit going for more than 1.5 hours. My boss

threatened to toss me and the Toshiba out a window every time the unit started

beeping during our usual marathon meetings. The Toshiba also had an active pen

which took four button batteries to operate. During a test of a preproduction

model, Vinny actually had one explode in his hand. The Toshiba representative

commented that they sort of did that occasionally. The potentially ballistic pen

was otherwise very easy to use and rode in it own silo when not in use. The 80 MB

disk was ample and a complement of port allowed floppy drive, keyboard, and

printer to be attached. I got to use it for about an month and had to give it

back just about the time my boss issued orders that it be banned from our staff

meetings. After its inital ailment, the GRiD Convertible never worked for more

than a week or two at a time. A conventional laptop finally took its place.

Fortunately, my old pen pal Vinny from IS heard of my misfortune and gracefully

agreed to let me test drive a brand new Toshiba T200. By then Vinny was working

for me, so I suspect his motives were advanced by his employment status. Of

course, he also knew that I would test the unit to death. The T200 was a

beautifully crafted computer, with smooth rounded corners, and barely larger than

its 9.5-inch diagonal monochrome VGA display. The Toshiba used an NiMH battery to

give it longevity. And that it would have had the Toshiba engineers kept it a

decent size. Instead they reduced the battery to the size of a pack of

cigarettes, far too small to keep the unit going for more than 1.5 hours. My boss

threatened to toss me and the Toshiba out a window every time the unit started

beeping during our usual marathon meetings. The Toshiba also had an active pen

which took four button batteries to operate. During a test of a preproduction

model, Vinny actually had one explode in his hand. The Toshiba representative

commented that they sort of did that occasionally. The potentially ballistic pen

was otherwise very easy to use and rode in it own silo when not in use. The 80 MB

disk was ample and a complement of port allowed floppy drive, keyboard, and

printer to be attached. I got to use it for about an month and had to give it

back just about the time my boss issued orders that it be banned from our staff

meetings. After its inital ailment, the GRiD Convertible never worked for more

than a week or two at a time. A conventional laptop finally took its place.

By Fall of 1993, I had become seriously depressed over my return into the

dark age of pen and paper. My boss was delighted that my Mont Blanc and notepad

never beeped but I was miserable. That's when I started reading more and more

about PDAs. I became fixated on choosing my next weapon for the war on paper and

spent weeks comparing the features of the two leading PDA architectures, those of

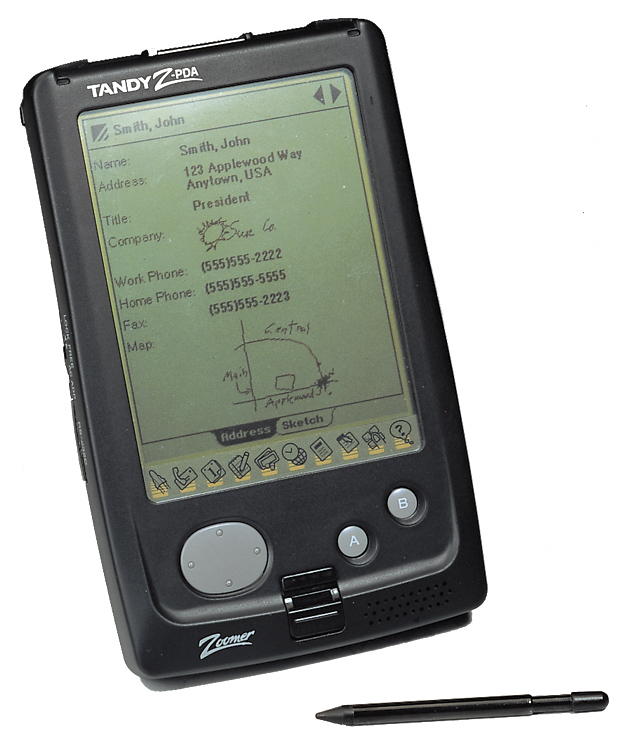

Apple's Newton and Casio's Zoomer. (The Casio Zoomer was also sold as the Tandy Zoomer (shown left); Note how the Zoomer's design

carries over to today's Cassiopeia Pocket PCs.). After much reading I concluded that my PDA had

to be able to do what none of my computers I had ever done successfully: It had

to translate my handwriting into text. Every since grammar school I knew that my

retention skyrocketed whenever I took notes. Hence my main application for the

PDA would be note taking. The recognition was essential because not only did I

actually want to be able to read the notes afterwards, I wanted to be able to

store and retrieve them and share them with others, which necessitated ASCII

text. Ink would only be good in a pinch. Since character-by-character recognition

on pen computers was a poor match for my sloppy writing, I decided that the

Newton's word-based recognizer was the way to go.

By Fall of 1993, I had become seriously depressed over my return into the

dark age of pen and paper. My boss was delighted that my Mont Blanc and notepad

never beeped but I was miserable. That's when I started reading more and more

about PDAs. I became fixated on choosing my next weapon for the war on paper and

spent weeks comparing the features of the two leading PDA architectures, those of

Apple's Newton and Casio's Zoomer. (The Casio Zoomer was also sold as the Tandy Zoomer (shown left); Note how the Zoomer's design

carries over to today's Cassiopeia Pocket PCs.). After much reading I concluded that my PDA had

to be able to do what none of my computers I had ever done successfully: It had

to translate my handwriting into text. Every since grammar school I knew that my

retention skyrocketed whenever I took notes. Hence my main application for the

PDA would be note taking. The recognition was essential because not only did I

actually want to be able to read the notes afterwards, I wanted to be able to

store and retrieve them and share them with others, which necessitated ASCII

text. Ink would only be good in a pinch. Since character-by-character recognition

on pen computers was a poor match for my sloppy writing, I decided that the

Newton's word-based recognizer was the way to go.

By Thanksgiving of 1993, I was the proud owner of an original Newton MessagePad. Since I am a determined soul I suffered through the learning curve and achieved reasonable success on good days. As a note pad, the Newton worked well for me. I loved the schedule application and I trashed my Rolodex cards for the Newton's Names application. And I used the Newton modem to fax documents I wanted to print to nearby fax machines. Soon, I ordered the Printer Cable and the Connection Kit for Windows. With the printer cable, no printer was an island to my Newton. Between fax machines and PC and Apple printers, I could always produce paper on demand. However, it was the Connection Kit that really brought things to life because it made all of the Newton applications available to the PC desktop. Data can be shared and updated on either the Newton or the PC and then synchronized between the two. Even with its slow speed and quirky nature it was great. I turned my calendar over to my secretary and she did all the updates via PC. I synched with her PC several times each day for updates. We carefully avoided making double entries by ruling that she commanded my schedule while I commanded the notepad and names. All meeting schedules went to her for approval while changes to the names and notepad were up to me. As of April of 1995, I still use my Newton--now a 110--religiously and I own numerous software applications.

I am also contemplating yet another Pen Computer. A special one this time. Small, sleek, a real killer. One that will really fulfill the promise of pen computing. As soon as I find it, I'll let you know.